BRIEF OVER VIEW OF FIBER OPTIC

CABLE ADVANTAGES OVER COPPER:

• SPEED:

Fiber optic networks operate

at high speeds - up into the gigabits

• BANDWIDTH:

Large carrying capacity

• DISTANCE:

Signals can be transmitted further

without needing to be "refreshed" or strengthened.

• RESISTANCE:

Greater resistance to electromagnetic noise

such as radios, motors or other nearby cables.

• MAINTENANCE:

Fiber optic cables costs much less to maintain.

In recent years it has become apparent that

fiber-optics are steadily replacing copper wire

as an appropriate means of communication

signal transmission. They span the long

distances between local phone systems as well

as providing the backbone for many network

systems.

Other system users include cable television

services, university campuses, office buildings,

industrial plants, and electric utility companies.

A fiber-optic system is similar to the copper

wire system that fiber-optics is replacing.

The difference is that fiber-optics use light

pulses to transmit information down fiber lines

instead of using electronic pulses to transmit

information down copper lines. Looking at the

components in a fiber-optic chain will give

a better understanding of how the system works

in conjunction with wire based systems.

At one end of the system is a transmitter.

This is the place of origin for information

coming on to fiber-optic lines. The transmitter

accepts coded electronic pulse information

coming from copper wire. It then processes and

translates that information into equivalently

coded light pulses.

A light-emitting diode (LED) or an

injection-laser diode (ILD) can be used for

generating the light pulses. Using a lens,

the light pulses are funneled into the fiber-optic

medium where they travel down the cable.

The light (near infrared) is most often 850nm for

shorter distances and 1,300nm for longer

distances on Multi-mode fiber and 1300nm for

single-mode fiber and 1,500nm is used for for

longer distances.

Think of a fiber cable in terms of very long

cardboard roll (from the inside roll of paper

towel) that is coated with a mirror on the inside.

If you shine a flashlight in one end you can see

light come out at the far end - even if it's been

bent around a corner.

Light pulses move easily down the fiber-optic

line because of a principle known as total

internal reflection. "This principle of total internal

reflection states that when the angle of

incidence exceeds a critical value, light cannot

get out of the glass; instead, the light bounces

back in. When this principle is applied to the

construction of the fiber-optic strand, it is

possible to transmit information down fiber

lines in the form of light pulses. The core must a

very clear and pure material for the light or in

most cases near infrared light (850nm, 1300nm

and 1500nm). The core can be Plastic (used

for very short distances) but most are made

from glass. Glass optical fibers are almost

always made from pure silica, but some other

materials, such as fluorozirconate,

fluoroaluminate, and chalcogenide glasses, are

used for longer-wavelength infrared

applications.

There are three types of fiber optic cable

commonly used: single mode, multimode and

plastic optical fiber (POF).

Transparent glass or plastic fibers which allow

light to be guided from one end to the other with

minimal loss.

Fiber optic cable functions as a "light guide,"

guiding the light introduced at one end of the

cable through to the other end. The light source

can either be a light-emitting diode (LED))

or a laser.

The light source is pulsed on and off, and

a light-sensitive receiver on the other end of

the cable converts the pulses back into the

digital ones and zeros of the original signal.

Even laser light shining through a fiber optic

cable is subject to loss of strength, primarily

through dispersion and scattering of the light,

within the cable itself. The faster the laser

fluctuates, the greater the risk of dispersion.

Light strengtheners, called repeaters, may be

necessary to refresh the signal in certain

applications.

While fiber optic cable itself has become

cheaper over time - a equivalent length of

copper cable cost less per foot but not in

capacity. Fiber optic cable connectors and the

equipment needed to install them are still more

expensive than their copper counterparts.

Single Mode cable

is a single stand (most applications use 2

fibers) of glass fiber with a diameter of 8.3 to

10 microns that has one mode of transmission.

Single Mode Fiber with a relatively narrow

diameter, through which only one mode will

propagate typically 1310 or 1550nm. Carries

higher bandwidth than multimode fiber, but

requires a light source with a narrow spectral

width. Synonyms mono-mode optical fiber,

single-mode fiber, single-mode optical

waveguide, uni-mode fiber.

Single Modem fiber is used in many

applications where data is sent at multi-

frequency (WDM Wave-Division-Multiplexing)

so only one cable is needed - (single-mode on

one single fiber)

Single-mode fiber gives you a higher

transmission rate and up to 50 times more

distance than multimode, but it also costs more.

Single-mode fiber has a much smaller core

than multimode. The small core and single

light-wave virtually eliminate any distortion that

could result from overlapping light pulses,

providing the least signal attenuation and the

highest transmission speeds of any fiber cable

type.

Single-mode optical fiber is an optical fiber in

which only the lowest order bound mode can

propagate at the wavelength of interest typically

1300 to 1320nm.

jump to single mode fiber page

Multi-Mode cable

has a little bit bigger diameter, with a common

diameters in the 50-to-100 micron range for the

light carry component (in the US the most

common size is 62.5um). Most applications in

which Multi-mode fiber is used, 2 fibers are

used (WDM is not normally used on multi-mode

fiber). POF is a newer plastic-based cable

which promises performance similar to glass

cable on very short runs, but at a lower cost.

Multimode fiber gives you high bandwidth at

high speeds (10 to 100MBS - Gigabit to 275m

to 2km) over medium distances. Light waves

are dispersed into numerous paths, or modes,

as they travel through the cable's core typically

850 or 1300nm. Typical multimode fiber core

diameters are 50, 62.5, and 100 micrometers.

However, in long cable runs (greater than 3000

feet [914.4 meters), multiple paths of light can

cause signal distortion at the receiving end,

resulting in an unclear and incomplete data

transmission so designers now call for single

mode fiber in new applications using Gigabit

and beyond.

The use of fiber-optics was generally not

available until 1970 when Corning Glass Works

was able to produce a fiber with a loss of 20

dB/km. It was recognized that optical fiber

would be feasible for telecommunication

transmission only if glass could be developed

so pure that attenuation would be 20dB/km or

less. That is, 1% of the light would remain after

traveling 1 km. Today's optical fiber attenuation

ranges from 0.5dB/km to 1000dB/km

depending on the optical fiber used.

Attenuation limits are based on intended

application.

The applications of optical fiber

communications have increased at a rapid

rate, since the first commercial installation of a

fiber-optic system in 1977.

Telephone companies began early on,

replacing their old copper wire systems with

optical fiber lines. Today's telephone

companies use optical fiber throughout their

system as the backbone architecture and as

the long-distance connection between city

phone systems.

Cable television companies have also began

integrating fiber-optics into their cable systems.

The trunk lines that connect central offices have

generally been replaced with optical fiber.

Some providers have begun experimenting

with fiber to the curb using a fiber/coaxial

hybrid. Such a hybrid allows for the integration

of fiber and coaxial at a neighborhood location.

This location, called a node, would provide the

optical receiver that converts the light impulses

back to electronic signals. The signals could

then be fed to individual homes via coaxial

cable.

Local Area Networks (LAN) is a collective

group of computers, or computer systems,

connected to each other allowing for shared

program software or data bases. Colleges,

universities, office buildings, and industrial

plants, just to name a few, all make use of

optical fiber within their LAN systems.

Power companies are an emerging group that

have begun to utilize fiber-optics in their

communication systems. Most power utilities

already have fiber-optic communication

systems in use for monitoring their power grid

systems.

Fiber

by John MacChesney - Fellow at Bell

Laboratories, Lucent Technologies

Some 10 billion digital bits can be transmitted

per second along an optical fiber link in

a commercial network, enough to carry tens of

thousands of telephone calls. Hair-thin fibers

consist of two concentric layers of high-purity

silica glass the core and the cladding, which

are enclosed by a protective sheath. Light rays

modulated into digital pulses with a laser or

a light-emitting diode move along the core

without penetrating the cladding.

The light stays confined to the core because the

cladding has a lower refractive index—

a measure of its ability to bend light.

Refinements in optical fibers, along with the

development of new lasers and diodes, may

one day allow commercial fiber-optic networks

to carry trillions of bits of data per second.

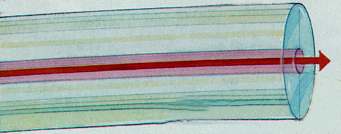

Total internal refection confines light within

optical fibers (similar to looking down a mirror

made in the shape of a long paper towel tube).

Because the cladding has a lower refractive

index, light rays reflect back into the core if they

encounter the cladding at a shallow angle (red

lines). A ray that exceeds a certain "critical"

angle escapes from the fiber (yellow line).

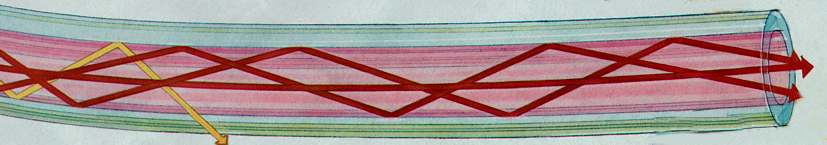

STEP-INDEX MULTIMODE FIBER

has a large core, up to 100 microns in

diameter. as a result, some of the light rays that

make up the digital pulse may travel a direct

route, whereas others zigzag as they bounce off

the cladding. These alternative pathways cause

the different groupings of light rays, referred to

as modes, to arrive separately at a receiving

point. The pulse, an aggregate of different

modes, begins to spread out, losing its

well-defined shape. The need to leave spacing

between pulses to prevent overlapping limits

bandwidth that is, the amount of information that

can be sent. Consequently, this type of fiber is

best suited for transmission over short

distances, in an endoscope, for instance.

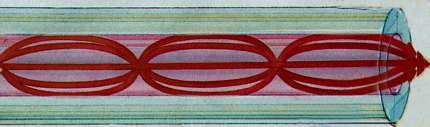

GRADED-INDEX MULTIMODE FIBER

contains a core in which the refractive index

diminishes gradually from the center axis out

toward the cladding. The higher refractive index

at the center makes the light rays moving down

the axis advance more slowly than those near

the cladding. Also, rather than zigzagging off

the cladding, light in the core curves helically

because of the graded index, reducing its travel

distance. The shortened path and the higher

speed allow light at the periphery to arrive at a

receiver at about the same time as the slow but

straight rays in the core axis. The result: a

digital pulse suffers less dispersion.

SINGLE-MODE FIBER

has a narrow core (eight microns or less), and

the index of refraction between the core and the

cladding changes less than it does for

multimode fibers. Light thus travels parallel to

the axis, creating little pulse dispersion.

Telephone and cable television networks install

millions of kilometers of this fiber every year.

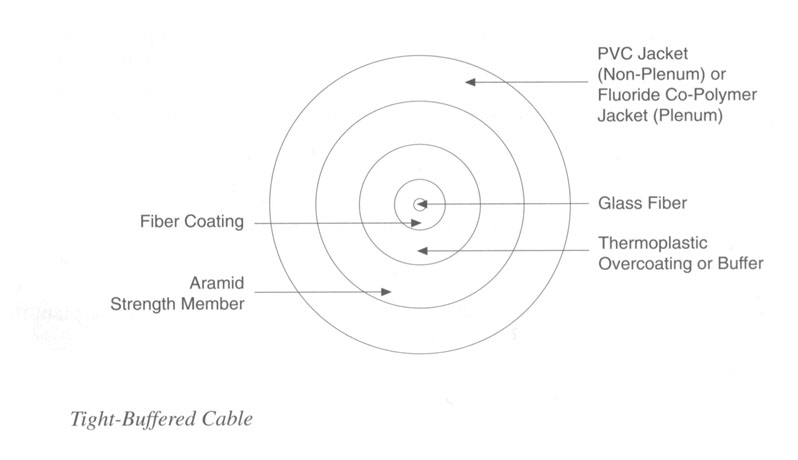

BASIC CABLE DESIGN

1 - Two basic cable designs are:

Loose-tube cable, used in the majority of outside-plant installations in North America, and tight-buffered cable, primarily used inside buildings.

The modular design of loose-tube cables typically holds up to 12 fibers per buffer tube with a maximum per cable fiber count of more than 200 fibers. Loose-tube cables can be all-dielectric or optionally armored. The modular buffer-tube design permits easy drop-off of groups of fibers at intermediate points, without interfering with other protected buffer tubes being routed to other locations. The loose-tube design also helps in the identification and administration of fibers in the system.

Single-fiber tight-buffered cables are used as pigtails, patch cords and jumpers to terminate loose-tube cables directly into opto-electronic transmitters, receivers and other active and passive components.

Multi-fiber tight-buffered cables also are available and are used primarily for alternative routing and handling flexibility and ease within buildings.

In a loose-tube cable design, color-coded plastic buffer tubes house and protect optical fibers. A gel filling compound impedes water penetration. Excess fiber length (relative to buffer tube length) insulates fibers from stresses of installation and environmental loading. Buffer tubes are stranded around a dielectric or steel central member, which serves as an anti-buckling element.

The cable core, typically uses aramid yarn, as the primary tensile strength member. The outer polyethylene jacket is extruded over the core. If armoring is required, a corrugated steel tape is formed around a single jacketed cable with an additional jacket extruded over the armor.

Loose-tube cables typically are used for outside-plant installation in aerial, duct and direct-buried applications.

With tight-buffered cable designs, the buffering material is in direct contact with the fiber. This design is suited for "jumper cables" which connect outside plant cables to terminal equipment, and also for linking various devices in a premises network.

Multi-fiber, tight-buffered cables often are used for intra-building, risers, general building and plenum applications.

The tight-buffered design provides a rugged cable structure to protect individual fibers during handling, routing and connectorization. Yarn strength members keep the tensile load away from the fiber.

As with loose-tube cables, optical specifications for tight-buffered cables also should include the maximum performance of all fibers over the operating temperature range and life of the cable. Averages should not be acceptable.

Connector Types

Gruber Industries

cable connectors

here are some common fiber cable types